Test-Driven Development: A Double-Edged Sword

Is TDD really worth the time to invest for a maintainable and clean codebase

tddArticle Index

Double-Edged Sword: something that has or can have both favorable and unfavorable consequences

Test-driven development (TDD), undoubtedly one of the most powerful way to keep any codebase clean, sustainable, and maintainable, especially in the long run. Unlike programming paradigms, this process or practice can be implemented in any project. Of course, with great benefits comes at a great cost, and it is certainly not a silver bullet nor a one-size fits all type. Just because it can be used in any project, does it mean you should?

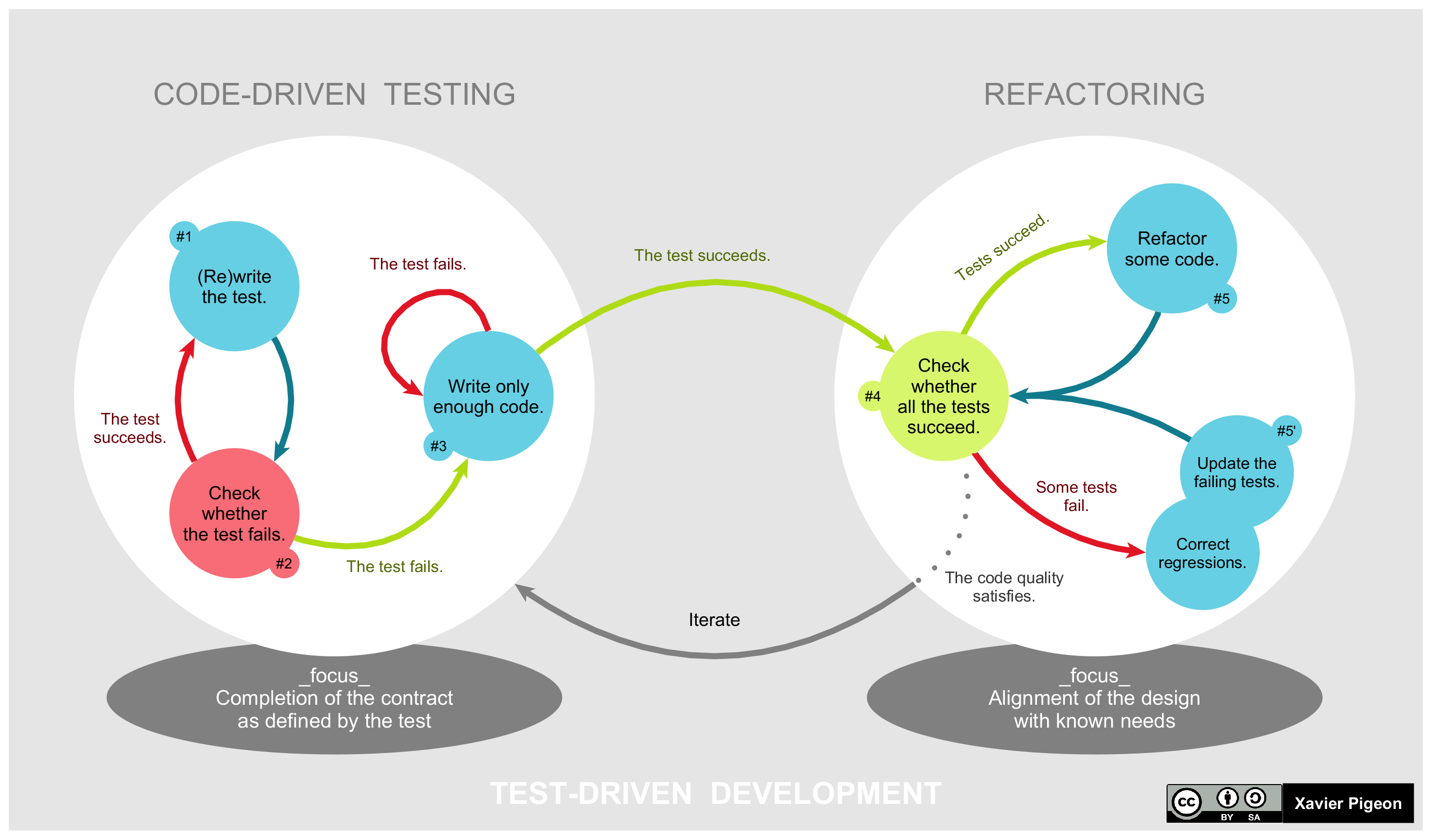

Test-driven development

Of course, obligatory Uncle Bob’s 3 Rules of TDD when writing anything TDD related

- You are not allowed to write any production code unless it is to make a failing unit test pass.

- You are not allowed to write any more of a unit test than is sufficient to fail; and compilation failures are failures.

- You are not allowed to write any more production code than is sufficient to pass the one failing unit test.

By definition, any team following the TDD cycle must not write any production code before writing a failing unit test, you cannot write more unit test than needed for the next production code, and you shall only write production code sufficient enough to pass the failing test written then.

Now you know what TDD is. So, why even bother doing this all of this work? Isn’t writing code complicated enough already, now we’re supposed to follow this set of rules with steps like writing a test beforehand and only write code to pass it.

Well, let’s take a look at the (expected) benefits first shall we. There’s definitely more depending on how you look at it, but here’s a few common and most helpful ones

- Significant reduction in defect rates; since everything is tested, there will certainly be less bugs and unexpected errors that makes the production app unusable.

- Less misses in acceptance criteria; since you’ll be listing all of it at the start to decide what the team will be working on, you’ll make sure everything on the list is processed.

- No more worries when refactoring; since this will only happen after the test and production code has been written, any refactors that breaks the app will be caught immediately by the test.

- Documentation without documenting; the tests written acts as the team’s documentation, it provides a much cleaner and verbose way to understand what a code is doing by looking at the test rather than having comments written between codes.

As you can see, it clearly is a good practice to follow TDD cycle. The benefits are undoubtedly so good for the health of your codebase, especially on the long run. But, hear me out first because I mentioned that this isn’t a silver bullet. We can’t just always use this on every project. I’ll elaborate in the later section of this post.

Testing, coverage, and QA package

TDD is focused around making test to reduce defect rates at the cost of increased initial development effort and time. To make this cycle works, we also need a certain setup to aid this cycle. This is the basic test, coverage, and QA package.

In my previous post, I mentioned that my team and I are working on building a mobile app using Flutter. Of course, as a student they won’t let us off that easily, our professors and their assistant won’t accept us by just creating a production-ready app, they want us to maintain our code too, combine all of our previous knowledge from various courses and apply everything we can to this course. Yes, including design patterns, practices, methodologies, and all that good stuff.

We first start by setting up a pipeline to help automate our development cycle, this is where devops shine, though it’s usually a setup and forget type of job. We’ll only discuss the general idea here, I’ve covered this a lot more detailed in my previous post so go check it out if you’d like too.

Simply put, our pipeline will

- Lint the code before test (Optional, could be run parallel with test); this will make sure all written code follows the determined rules to conform its language definition of clean code before testing anything. In our case,

analysis_options.yaml - Test the code every time it’s pushed to our development branch; this will make sure all our production code passed the test, or the newly written test fails.

- Create a coverage overview; in our case, we pass an artifact from our previous job, which is the test, to create a coverage overview for us to see. While at the same time, forwarding our code to a SonarQube remote server using SonarScanner.

With just 3 of these steps, we’re actually done with our TDD pipeline setup, this is the full test-code-pass cycle. Now, you might’ve noticed we’re using a third-party provider for our code analysis step in the third step, you can actually use anything else. In fact, students before us were graded manually by the assistants. It was quite controversial since it would be a subjective matter and depends heavily on their knowledge and… their current mood. Yeah, even 2 students with the exact same code might not get the same points.

Since we’re the first batch to use a third-party provider to grade our code quality, it’s pretty hard to debug when something goes wrong since there’s only a few people experienced enough to know what the problem is. Not to mention, our local repository definition of good code quality vs the server’s definition could also differ since they have their own options file. This was quite a struggle for us too, but it everything was an new (debugging) experience and therefore increases our skills. Expect these kinds of things to happen too.

The last part of this package is usually tested by the product owner or client itself. Although, you’ll usually want to test it first by just matching it with the current acceptance criteria before presenting it to the client.

Software development life cycle

Software development life cycle (SDLC) is a formalized methodology framework, considered to be the oldest one. Currently, this process is known by many name, including software development process or software development methodology.

Its practices is already commonly known by us. This includes stuff like continuous integration used by extreme programming (XP), software prototyping, incremental development, and rapid application development (RAD).

Its methodologies is also already commonly known by us. Some famously known

- Agile development; which is widespread and exercised by Trello and other companies that uses kanban and scrum boards.

- Waterfall development; considered as an old-school method which doesn’t fit with the current rising startup because of the inflexibility that requires its client to exactly plan everything at the start with no changes until the end.

- Spiral development; combines the aspect of waterfall methodology and RAD practice.

- Behavior-driven development (BDD); an extension of TDD

There’s still a lot more others for sure, but all of this falls under SDLC. One in particular, which our course uses is Agile development. Wait, didn’t you say you’re using TDD? I hear you say, and that is correct too. Keep in mind that Agile is the methodology framework and TDD is the practice. One is how we plan it and the latter is how we implement it.

Agile software development

By that definition alone, some of you might see a certain flaw in our practice. Let’s take a look what agile in software development is

Its manifesto consists of 4 main points

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools Working software over comprehensive documentation Customer collaboration over contract negotiation Responding to change over following a plan

Agile software development itself is more than frameworks. It uses either scrum, XP, or feature-driven development (FDD), all of which are basically the same, fundamentally. But, it follows many practices which is pair programming, TDD, stand-ups, planning sessions, and sprints.

- Pair programming; this has been done a lot since we’re feature-heavy and almost all of it is dependent between each other. We split each feature to 1 or 2 person and work on it together before working on the next one.

- TDD; to which I’ve mentioned in the previous section thoroughly.

- Stand-ups; a “daily” meeting between the scrum master (one in charge to oversee) and the dev team. Usually to keep track of progress and not lost contact of said person.

- Planning sessions; usually done immediately after a sprint meeting to decide what to work on for the next weeks before the next sprint meeting.

- Sprint meeting; a meeting to present the final product according to the acceptance criteria chosen weeks before that. This is the final step of QA from the client before they decide if the application is ready for production release.

Now, keep in mind that these are the practices we actually followed and implement in our sprints. Scrum itself actually has a so-called “Pillars” which it stands by and uses as its foundation. It’s the official events for scrum framework which consists of

- Sprint planning; done before each sprint, also called planning sessions by some.

- The sprint; or the scrum itself which some might’ve forgot about, the time period where the team actually develops the application.

- Daily scrum meetings; a, give or take, 15-minute meeting for the team, supposedly done daily to create a plan for the next 24 hours. Also known as some by stand-ups.

- Sprint review; is held at the end of every sprint and its objective is to obtain feedback. The scrum team and the stakeholders collaborate and discuss what was done in the sprint.

- Sprint retrospective; a meeting held after sprint reviews and usually prior to sprint plannings. It usually takes 1 to 2 hours for 2-week duration sprint and 3 to 4 hours for one month duration sprints.

My team and I have successfully managed to tackle various kinds of problems using these practices. Pair programming for instance results in a more verbose working software with meaningful variables instead of plain comment documentation. It gives the other person that’s not actively coding some room to think and see a wider view of the code, hence improving the quality of code produced significantly.

Stand-ups on the other hand, reminds us to always move forward and keep progressing every day. We’re supposed to do this every day, since it literally has the name daily in it and its purpose is to plan for the next 24 hours. But then again, we’re students and we have a lot of other things to do, so we’re doing it every 2 to 3 days. We share our progress of what we’ve done since the last stand-up, we share our hardships and how we overcome it, and we hear what our team members are doing and what they struggle with. The stand-ups isn’t particularly amazing on itself, but the consistency and habit we build up is what matters in a team project.

Planning sessions are the first steps of our success in that sprint as well. We spend around 3 to 5 hours to list and breakdown what we’re going to do into smaller and individual tasks according to the next features to fullfil the acceptance criteria. By doing this, we make sure everyone gets the appropriate task according to their skills and eagerness. We also know who needs help on which task so there can be 2 people assigned to it.

Sprint reviews is a somewhat nerve-racking agenda for us every time it comes up, even though we already finished the product and tested the features to meet the acceptance criteria. There’s always 1 or 2 people working on the presentation while the others double-check the final product again to make sure everything’s fine and prepare the product to be presented. Usually, we always find 1 or 2 things gone wrong 2 to 3 hours beforehand, but that’s what why we do double-checks right. Of course, its objective is to obtain feedback from the stakeholders, but it also decides our fate for the next sprint, since we’re students, this agenda also grades our scores for the current sprint and decides if we pass or fails by looking at how much of the criteria is accepted from our chosen product backlogs. That’s why we’re pretty nervous when it comes to it.

Lastly, sprint retrospectives. We’re not too diligent on doing this exactly after each sprint reviews because our scrum master is busy attending another team’s sprint review. So, we held our sprint planning on our own first and wait for 1 or 2 days for the sprint retrospective with our scrum master. My team and I really doesn’t have any problem with each other, thankfully, since we always passed all the previous sprint reviews successfully. Even though it took us many sleepless nights and hours, it always seemed enough to finish. That’s why we have a lot more good things to discuss rather than the bad ones.

Our scrum master does a really great job of reminding us and keeping the team together. It is somewhat crucial to have a person that’s not actively developing to oversee the development team, because there are times when we ran into something huge blocking our progress for an extensive amount of time and that is where scrum masters are needed the most.

Time-driven development

I’ve mentioned this in my previous post too, this is by no means a formal methodology or practice to follow upon. But, I feel this suits us perfectly, as students working on an app within a fixed amount of time, given a set amount of features to complete, and still conforming to our responsibilities as college students.

Disclaimer: Before I go any further, I am by no means declaring that the practice of TDD is useless, considering the conditions my team and I are in, this practice just does not fit in well

TDD as a double-edged sword still applies to any projects there is out there, but I’ll be discussing this according to my team’s current project and why it is crucial to define your priorities beforehand.

Let’s start by looking at the conditions first, shall we.

- We’re building a mobile app where only one of our member has lightly experienced working with a mobile environment (no complaints though, since new things are always exciting, except when), including an admin page that requires a web environment.

- We’re given 5 sprints to complete the project, with each sprint ranging out to 2 weeks each, so 10 weeks in total or 2 and a half months.

- There are 21 features to complete within that period of time, with another 3 additional ones added in after our 3rd sprint, so a total of 24 features.

- In between each sprint, there’s another meeting called Individual Review (IR) which requires us to wrote a mandatory article to fullfil a competence row in the excel sheet to tests our written knowledge, as well as some verbal ones by discussing it through a one-to-one meeting with our professor in that time.

- All of which are done while still doing our responsibilities as a student

Of course, there won’t be a problem if this is a job, with the exact same constraints. But, a job is focused on one thing and it is to develop the app.

Time-driven development is what I proposed. It adapts according to the current job with the highest priority for that time. One sprint, there might be so much stuff to do that writing tests is just not feasible, so the priority changes to finishing the current features. Another sprint might not be that feature-heavy so previous features can have tests written for it.

As an experienced programmer, writing test might be as easy as printing “hello world”. But, for a team writing an app while learning its language could be quite the challenge, given they’re racing against time, writing tests could be like running in the water to a certain extent. It just slows down the development process.

There’s a lot of thought put in to following TDD practice when you’re still learning.

Is it really worth it to learn how to write test when I’m not even sure how I’m going to approach this problem or that feature?

or Oh no, I’ve only got 12 more hours before the next sprint meeting, and there’s still 1 to 2 more features to finish, am I really gonna waste my time to write tests I haven’t yet understand?

Of course, it doesn’t mean you should completely abandon TDD, especially if you know it’s going to be a long-term project and a lot of people would be working on it. But, when you’re only given 2 weeks to make a full-fledged website from scratch when you’ve been working on mobile previously and will work on mobile again after those 2 weeks, it may be wise to rethink your sprint priorities carefully.

TDD will definitely make your life easier in the foreseeable future, but its lengthy initial development time and effort you need to put in to may be your downfall right now

Reference(s):

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Test-driven_development

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_development_process

- https://itnext.io/test-driven-development-in-flutter-e7fe7921ea92

- http://www.butunclebob.com/ArticleS.UncleBob.TheThreeRulesOfTdd

- https://www.agilealliance.org/glossary/tdd/

- https://www.madetech.com/blog/9-benefits-of-test-driven-development

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agile_software_development

- https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/

- https://agilemanifesto.org/iso/en/manifesto.html

- https://mauss.dev/posts/complete-flutter-development-automation/